19 You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe-and shudder!

This is one of the most misunderstood verses in the Bible and the confusion which surrounds it is so pervasive that it is difficult to fully express the magnitude of its impact on the church. It is frequently cited to argue that belief, defined as knowledge with assent or understanding with assent, in the gospel is not enough to save, but that one must also have trust or commitment. This is inferred from the simple fact that the demons believe and perish.

To illustrate this view let’s consider the writings of William Webster in his book The Church Of Rome at the Bar of History.

For faith to be truly biblical, it must involve more than just the assent of the mind to objective truth about God, Christ, and salvation… Faith is foundational to true Christianity and it involves knowledge, assent, trust, and commitment.

...the Epistle of James warns us against a faith which is empty and vain; that is one that acknowledges the objective facts of God, Christ, and salvation to be true but negates or neglects the other essential element of trust and commitment. The demons believe in that sense, but they perish (James 2:19). Intellectual assent alone is empty, James argues.[i]

Webster argues that according to James, intellectual assent is empty and vain. It is not enough to acknowledge the objective facts of God, Christ, and Salvation to be true because we must also have the additional and “essential elements of trust and commitment.” He then refers to James 2:19 and concludes that the demons believe in that sense but they perish. Likewise R.C. Sproul stated

“According to James, even if I am aware of the work of Jesus, convinced intellectually that Jesus is the Son of God, that he died on the cross for my sins, and that he rose from the dead, I would at that point qualify to be a demon.”[ii]

Webster’s and Spoul’s understanding of this verse is partly influenced by the Latin threefold definition of faith, which is noticia (knowledge), assensus (assent), and fiducia (trust). The vast majority of English speaking Reformed theologians use the threefold definition of faith. The third element fiducia is most commonly translated as trust, but it has also variously been translated as commitment, obedience, repentance, resting, transformation, etc. This understanding of faith is deeply rooted in the Reformed tradition, but it has also been vigorously put forth by the proponents of Lordship Salvation in an effort to combat the antinomianism of the free grace movement. The view that one can be saved by belief alone, defined as knowledge and assent or understanding with assent, is often denigrated as easy-believism, and we are told that mere intellectual assent is insufficient to save. Doug Barnes argues that “salvation is by faith alone in Christ alone, but ‘faith alone’ is not ‘belief alone,’” and therefore he concludes that “belief alone is not enough.”[iii]

None of these men have understood James’ point, and their use of the Latin definition of faith has led them to eisegete a wrong view into this text. Unfortunately this has resulted in multiple problems which can be challenging to sift through. Therefore we will deal with this in three parts. First we will address the improper use of the Latin definition. Then we will show the invalid conclusions of the views already expressed and we will walk out their logical implication. Finally, we will explain what James actually meant.

The Latin Definition

This Latin definition of faith as noticia (knowledge or understanding), assensus (assent) and fiducia (trust) may seem appropriate for several reasons. First, from a cursory reading, it would appear that James says that belief alone is not enough to save. Obviously the demons know and assent to the truth but they perish. Secondly, it is right to advocate for a personal trust in Christ. One cannot be saved unless they trust in Jesus. So what’s the problem then? Why would we disagree with what Sproul, Webster, and Barnes said?

Their arguments rest on the notion that belief is different from faith because it lacks trust. They therefore define belief as noticia (knowledge or understanding) with assensus (assent) and they define faith as noticia (knowledge or understanding), assensus (assent) and fiducia (trust or commitment). The problem is that the Bible was not written in Latin. The New Testament was written in Greek and both of the words faith and belief are translated from the same Greek word pistis. This is why Luke Miner has pointed out that “these are not two different concepts in Greek but one (“faith” and “belief” are just alternate translations of the Greek word πιστiς). That these are interchangeable concepts is suggested by the fact that Bible translations will commonly use ‘faith’ in place of ‘belief’ or ‘have faith’ in place of ‘believe.’”[iv]

If the words faith and belief are translated from the same Greek word throughout the New Testament then there is no Biblical precedent for defining them differently when we arrive at James 2:19. This means that faith and belief are both defined as understanding with assent. This is what Gordon Clark argued for in his definition of faith. In What Is Saving Faith? he explained that “Faith, by definition, is assent to understood propositions. Not all cases of assent, even assent to Biblical propositions, are saving faith, but all saving faith is assent to one or more Biblical propositions.”[v]

This of course leaves a lingering question: What about the third essential element of fiducia (trust)? How can we say that we are saved by faith alone if it is defined only as noticia (knowledge or understanding) and assensus (assent)? Didn’t we already admit that fiducia (trust) was necessary for salvation? It appears contradictory to say that one must have trust to be saved and that we are saved by faith or belief alone which are defined only as understanding with assent. John Robbins however explained that “Belief, that is to say, faith (there is only one word in the New Testament for belief, pistis) and trust are the same; they are synonyms. If you believe what a person says, you trust him. If you trust a person, you believe what he says. If you have faith in him, you believe what he says and trust his words.”[vi] In other words, trust is synonymous with belief and this is why it is wrong to suggest that one can believe and not trust. To argue that we need trust in addition to belief is simply redundant. This is why Clark argued that adding fiducia to faith is a tautology:

The crux of the difficulty with the popular analysis of faith into noticia (understanding), assensus (assent), and fiducia (trust), is that fiducia comes from the same root as fides (faith). Hence this popular analysis reduces to the obviously absurd definition that faith consists of understanding, assent, and faith. Something better than this tautology must be found.[vii]

Fiducia (trust) is frequently put forth as an extra “psychological” element that many Protestants add to faith which Clark and Robbins tirelessly refuted as confused, meaningless, and redundant. To conclude from this verse that belief is more than understanding with assent and therefore trust is necessary in addition to belief is logically invalid. This will lead us into the next section as we expose the invalid conclusion and their logical implications.

The Invalid Inference

Notice that neither Sproul nor Webster actually quote James; but rather simply refer to this verse and then make an inference. They have inferred that belief in the gospel is insufficient to save because James says, “Even the demons believe and tremble!” Therefore something else is required. One must not only understand and assent, but also trust in the gospel in order to be saved. As we have already shown, this is confused, meaningless, redundant and unbiblical, but now we will show that it is logically invalid as well.

The reason their inferences are invalid and wrong is because James says nothing about demons acknowledging the “objective facts of God, Christ, and salvation to be true” as Webster stated. Nor does he say anything about the demons believing that Jesus "died on the cross for [their] sins, and that he rose from the dead” as Sproul stated. One could argue that they are putting their own words into James' mouth. Here again is what James actually says: "You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe-and shudder!"

As Dr. John Robbins pointed out, “James mentions only belief in one God - monotheism. Since belief in one God is belief in one true proposition, James says, ‘You do well.’ But monotheism is not saving belief because it is not about Jesus Christ and his work.”[viii] Dr. Gordon Clark also corrected this wrong inference: “[The] argument here is that since the devils assent and true believers also assent, something other than assent is needed for saving faith. This is a logical blunder. The text says the devils believe in monotheism.”[ix]

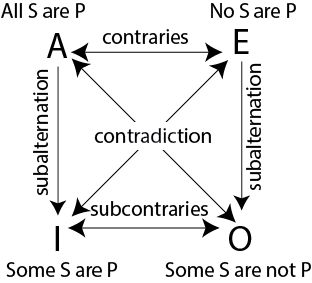

This of course is invalid because James says nothing about demons believing the gospel. But James does say however that they do believe. If then, one hopes to establish on the basis of this verse that the difference between those who are saved and those who are not saved rests in the necessary element of trust in addition to belief, then we are faced with three logically invalid conclusions. To show this, let’s accept, for the sake of argument that the demons are lost because they believe but do not trust, and therefore in order to be saved we must not only believe, but we must also trust. This logical blunder, which results from inferring something that isn’t there in the text, leads to three invalid conclusions. 1) Intellectual assent is different from trust. 2) Belief alone in the gospel is insufficient to save. 3) The demonic faith, or belief, lacks trust.

Assent and Trust

Immediately after citing James 2:19 in which lost demons are said to believe, Webster concludes “Intellectual assent alone is empty.” Clark however, pointed out that, “It is illogical to conclude that belief is not assent just because belief in monotheism does not save.”[x] James nowhere distinguishes the type of faith or belief between Christians and lost demons but rather the difference is the propositions which are believed. The proposition that the demons are said to believe is that there is one God, and it is clear from the fact that they tremble that they trust in the truthfulness of this proposition. When the demons encountered Jesus they “cried out, ‘What have you to do with us, O Son of God? Have you come here to torment us before the time?’" (Matthew 8:29) The demons cried out and asked if he was there to torment them because they believed or trusted that he could torment them. They do not trust him for salvation because it is not offered to them but they do trust that he can torment them. Therefore one cannot logically infer that the demons mentioned by James lack trust in the truthfulness of the proposition they are said to believe. This is why John Robbins pointed out that “to use the words believe and trust interchangeably is good English and sound theology because they are synonyms.”[xi]

Belief Alone is Insufficient

Let’s first remember the words of Doug Barnes when he asserted “faith alone is not belief alone” and then concluded that “Belief alone is not enough.” After giving Mr. Barnes a much needed rebuke for poor scholarship John Robbins offered a very simple and sound refutation of his conclusion:

It follows, does it not, that when Christ said, “For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have everlasting life,” that he was misleading Nicodemus? And when the Apostle Paul said, “Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and you shall be saved” he was misleading the jailer? One might quote scores of similar verses, but these two will do to show how far Barnes is from Christian soteriology. According to the Scriptures, belief of the Gospel, and only belief of the Gospel, saves.[xii]

The Scriptural refutations of Barnes’ position are enough to settle the matter but let’s provide the logical refutation for good measure. This view that belief is not enough would logically imply that some who believe the gospel are not saved, to which Robbins responded: “If faith consists of three elements – knowledge, assent (or belief), and trust – and if a person does not have faith unless all three elements are present, then unregenerate persons may understand and believe-assent to–the truth. In fact, those who advocate the three-element view insist that unregenerate persons may understand and believe the truth – their prime example of such persons is demons. But if unregenerate persons may believe the truth, then the natural man can indeed receive the things of the Spirit of God, for they are not foolishness unto him, contrary to 1 Corinthians 2 and dozens of other verses. Belief – and the whole of salvation – is not a gift of God. Natural men can do their own believing, thank you very much. The three-element view of faith leads straight to a contradiction – faithless believers – and therefore must be false.”[xiii]

Demonic Belief Lacks Trust

The views espoused by Webster, Sproul, and Barnes would logically imply that if demons had trust then they too would be saved. To conclude that belief, understanding and assenting to the propositions of the gospel, is not enough to save, from the fact that this does not save the demons, and that a third element of trust is required, logically implies that if the demons had this third element of trust, then they too would be saved. But that simply is not the case and therefore the whole argument falls apart. The reason the demons are not saved is because they have no savior. It is not because they don’t have the right kind of faith. It is invalid to deduce from this verse that belief (assenting to understood propositions) in the gospel is insufficient to save because James says nothing about demons believing the gospel. We have to remember that it is a basic rule of logical deduction that the content in the conclusion must be derived from one or more of the premises. Since verse 19 makes no mention of the demons assenting to understood propositions of the gospel we cannot logically deduce that understanding with assent to the propositions of the gospel is insufficient to save.

All of these conclusions are logically absurd. Therefore, the difference cannot be in a belief that is distinct from faith or trust. There are multiple reasons to reject this understanding of James 2:19, which is influenced by the imposition of a Latin definition and suggests that belief alone is insufficient to save.

The Bible was not written in Latin and the words faith and belief are both translated from the same Greek word pistis. There is therefore no Biblical precedent for defining them differently when we arrive at James 2:19.

Belief and faith are synonymous with trust and it is therefore wrong to suggest that one can believe and not trust.

Fiducia comes from the same root as fides (faith). Hence this popular analysis reduces to the obviously absurd definition that faith consists of understanding, assent, and faith. This is a tautology.

It is an invalid inference to conclude that belief in the gospel is not sufficient to save because James says the demons believe in monotheism.

This leads to an absurd contradiction that some who believe the Gospel will perish.

To argue that understanding and assent are not enough to save because it doesn’t save the demons, and that one needs the extra element of trust, logically implies that if the demons had this then they too would be saved.

What James Actually Meant

Why then does James bring up their belief that God is one and reference the demons? We have to remember the context of the passage and the broader context of the letter of James. This letter was written by James, the brother of Jesus (Matt. 13:55) and leader of the Jerusalem church (Acts 15). It was written around A.D. 40–45 to Jewish Christians living outside Palestine. James is speaking to Jewish converts and the immediate context of this passage shows that he is addressing a specific type of hypocrisy - religious hypocrisy.

Both Paul and James confront different issues with members from the same congregation of Jewish converts in Jerusalem. In the book of Galatians Paul confronts the Judaizes over the issue of legalism and he identifies them as the circumcision party that came from James in Gal 2:12. This was the same group that he and Barnabas contended with over the gospel in Acts 15, and it is the same group he anathematized in Galatians 1:6-9. James, however, is confronting the issue of antinomianism with members from the same congregation in Jerusalem. At first this may seem odd because we tend to think of legalism and antinomianism as antithetical to one another. But they are not so much antithetical to each other as they are antithetical to the gospel. Apart from the light of the gospel, legalism will produce antinomianism and vice versa.

This is because the natural man who rejects the gospel must attempt to establish his own righteousness by the law, and therefore become a legalist. But because he is unable to keep the law, and yet is self-righteous, he is an antinomian. This is why Jesus refers to the legalists who profess their good works to him at the last judgement as “workers of lawlessness” (Matthew 7:21-23).

The antinomianism James now confronts is made manifest by a form of religious hypocrisy amongst the members of this Jewish congregation. Therefore he references The Shema when he acknowledges, “You believe that God is one.”

The Shema was the most important prayer in Israel and it served as the centerpiece of the morning and evening Jewish prayer services. “The first verse encapsulates the monotheistic essence of Judaism: ‘Hear, O Israel: the LORD our God, the LORD is one’ (Hebrew: שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ יְהוָה אֶחָֽד׃), found in Deuteronomy 6:4. Observant Jews consider The Shema to be the most important part of the prayer service in Judaism.”[xiv] These Jewish converts would have immediately recognized James’ reference and they would have understood his point.

He was not saying that belief alone, understanding with assent, in the gospel is not enough to save, as some modern English speaking Christians tend to think. Instead, he was confronting their religious hypocrisy, and the sting of comparing their piety to that of the demons would have been understood as a clear indictment against them. It could even be said that the demons had a more proper response than these hypocrites because at least they trembled.

This is the key to understanding James’ point in this verse. Religious hypocrites that are in the visible church will tend to believe some measure of truth revealed in scripture. They therefore have a form of religious piety but not a transformed life, because in spite of the fact that they believe certain propositions to be true they do not believe the gospel. There is a type of religious faith which does not produce works because it is not a faith gifted by God and regeneration has not taken place. The difference however is not in the type of faith or belief, but in the propositions believed.

Sean Gerety draws out further valuable insight from the demons' trembling that helps us to understand the nature of religious hypocrisy in the visible church. Not only can false converts or religious hypocrites believe true propositions revealed in scripture, but they can also experience heartfelt passion or emotion from these beliefs. Gerety writes,

Another overlooked aspect of James is not only what the demons believe (God is one), but their reaction in response to this belief (trembling). James is teaching us that not only is belief in God and monotheism not enough to make someone a Christian, but the sincerity and “heartfelt” nature of that belief also isn’t something which saves a person — nor should we be fooled by such displays. Of course, this would put most Televangelists out of business. You might say James is providing an interesting refutation of the Kierkegaardian idea of “infinite passion” and the idea that it is the “passion” or conviction one brings to the objects of their beliefs that saves and not the propositions believed.[xv]

Gerety’s insight is extremely valuable in helping us to understand the nature and deception of false converts. Many people are deceived into thinking they are genuine believers precisely because they believe some measure of truth and they often display heartfelt emotions. Unfortunately this insight is lost on most theologians today because they have not taken the time to understand James. What’s worse is that they have insisted on perpetuating false notions of faith, and eisegete their wrong views into the text. This, no doubt, has plagued the church with much confusion.

[i] Webster, William, The Church of Rome at the Bar of History, by William Webster, Banner of Truth Trust, 1996, pp. 133–134.

[ii] Robbins, John W. “R. C. Sproul on Saving Faith.” Trinity Foundation, 2007, trinityfoundation.org/journal.php?id=238.

[iii] Barnes, Doug. “Gordon Clark and Sandemanianism.” Banner of Truth USA, 10 Jan. 2005, banneroftruth.org/us/resources/articles/2005/gordon-clark-and-sandemanianism/

[iv] Miner, Luke. “What Is It to Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ?” Trinity Foundation. Accessed February 14, 2020. http://trinityfoundation.org/journal.php?id=330.

[v] Gordon H. Clark, What Is Saving Faith? (Unicoi, TN: The Trinity Foundation, 2004), p. 88, http://www.trinitylectures.org/what-is-saving-faith-p-60.html. Emphasis ours. This book combines Faith and Saving Faith and The Johannine Logos into one volume.

[vi] Robbins, John W. “R. C. Sproul on Saving Faith.” Trinity Foundation, 2007, trinityfoundation.org/journal.php?id=238.

[vii] Gordon H. Clark, "Saving Faith", The Trinity Review (Dec 1979), http://www.trinityfoundation.org/journal.php?id=10

[viii] Robbins, John W. “R. C. Sproul on Saving Faith.” Trinity Foundation, 2007, trinityfoundation.org/journal.php?id=238.

[ix] Gordon H. Clark, What Is Saving Faith? (Unicoi, TN: The Trinity Foundation, 2004), p. 152

[x] Clark, What Is Saving Faith?, p. 153.

[xi] Robbins, John W. “R. C. Sproul on Saving Faith.” Trinity Foundation, 2007, trinityfoundation.org/journal.php?id=238.

[xii] Barnes, Doug. “Gordon Clark and Sandemanianism.” Banner of Truth USA, 10 Jan. 2005, banneroftruth.org/us/resources/articles/2005/gordon-clark-and-sandemanianism/.

[xiii] Robbins, John. “The Church.” Trinity Foundation. Accessed February 14, 2020. http://www.trinityfoundation.org/journal.php?id=83

[xiv] “Shema Yisrael.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, January 20, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shema_Yisrael.

[xv] Gerety, Sean. “Demonic Theology.” God's Hammer, May 1, 2009. https://godshammer.wordpress.com/2007/09/17/demonic-theology/?fbclid=IwAR1otzI0WaDJqDqv9Ue_uuSIQaB_NvL8h57NSLOC73ymG5zcy7YbeuGBlX8.