“There’s a historic battle going on now across the West, in Europe, America and elsewhere. It is globalism against populism. And you may loath populism, but I tell you a funny thing, it’s becoming very popular.”

As of January 31, 2020, Great Britain is no longer part of the European Union (EU). Britain’s success in parting ways with the EU, what is commonly called Brexit, short for British Exit from the EU, is the culmination of nearly 30 years of work by Britons opposed to the Maastricht Treaty, which the was signed by the U.K.’s conservative government in 1992, making Great Britain part of the EU.

In June 2016, a referendum was held asking voters whether they wanted to remain in the EU or leave. Despite a great deal of opposition from the establishment, the vote went 52% in favor of Brexit, with 48% electing to remain in the EU.

Although interests dedicated to keeping Britain in the EU worked hard to subvert Brexit, the resounding victory of the conservatives under the leadership of Boris Johnson on December 12, 2019, effectively guaranteed the success of Brexit.

In this post, I don’t intend to get into the weeds of the political process that brought about Brexit. Neither do I intend to write much about the principle figures who supported Brexit or opposed it. My aim here is to step back and to view Brexit in its larger historical context, that of conflict between the Protestant Westphalian World Order and the New World Order globalism of the Roman Catholic Church-State (RCCS).

Though very little attention has been paid to the religious aspect of Brexit by mainstream journalism, and though it may seem strange to some to speak of any relationship between the 16th century Protestant Reformation and the 21st century Brexit, this author holds that, not only is there a relationship between the Reformation and Brexit, but that the relationship is a close one. Indeed, it is not an overstatement to put the relationship in these terms: No Protestant Reformation, no Brexit. It’s that simple.

Globalism: Protestants Oppose, Catholics Embrace

On January 12, 2017, the Washington Post ran an article titled “Catholics like the European Union more than Protestants do. This is why,” in which political scientists Brent Nelsen and James Guth note the split between Protestants and Roman Catholic over the EU and explain the reasons for this phenomenon.

After commenting that there’s a great deal of skepticism about the role of religion in European politics, Brent Nelsen observed,

But in 2001, we started looking at Eurobarometer data, and it’s very clear that Catholics, controlling for all other factors, favor the E.U. more than do Protestants. These attitudes were forged in the Reformation, with the development of two different approaches to governance in Europe. Catholics see Europe as a single cultural whole that ought to be governed in some coordinated way. Protestants, on the other hand, have seen the nation state as a bulwark against Catholic hegemony, and they have been very reluctant to give it up, even as religion has become less important.

This is an excellent summary of the very distinct views of international relations held by Protestants and Romanists. Later in the article, Nelsen expands on this idea,

Catholicism has always been a universal religion. It was the successor to the Roman Empire, and in Catholic theology and ideology, there’s always been an emphasis on the unity of Christendom. Even today, even though the pope doesn’t claim secular authority, there’s still supranational governance within the Roman Catholic Church. So Catholics have always been very comfortable, even if subconsciously, with the notion of supranational governance.

After the Reformation, Protestants, on the other hand, attempted to carve out areas of religious liberty and caught on to the notion of the nation state. They didn’t invent the concept — it was invented by both sides as they came out of the religious wars of the 17th century — but the Protestants saw the nation state as very important for guaranteeing their liberty. For people in the Nordic states and the United Kingdom, the continent was the source of instability and of hegemony, and that’s part of why they developed a strong commitment to the nation and to national sovereignty — this was really the main vehicle for defense against, first, expanding Catholic control in the 16th and 17th centuries, and then, later on, Napoleon and Hitler.

We can summarize Nelsen’s comments thus: The Roman Catholic Church-State, as successor to the Roman Empire, believes in globalism, in empire building and in a top-down structure of world government, whereas Protestants view these ideas as tyrannical and see the nation-state as a bulwark against them and as a guarantor of personal liberty.

What Saith the Scriptures?

So who’s right in this conflict? Are Romanists calling for world government – it’s remarkable to this author that, despite the many, open, and aggressive calls for world government by popes and other high officials of the Roman Catholic Church-State, so little note is made of Rome’s push for globalism; this is true both among members of the mainstream media and the independent, alternate media; it’s as if reporters and pundits all have veils over their hearts when writing about Rome – in the right, or are Protestants who view the nation state as a bulwark against tyranny?

Very obviously, the Protestants have it right. So where are the Scriptural proofs? While this author does not claim to exhaust in this brief post all the Bible has to say in support of independent nation states and in opposition to globalist tyranny, it is possible to hit the highlights.

Empires are Monuments to Sinful Man’s Pride

The Tower of Babel is one early example of man’s sinful attempt to build a world empire as a monument to his own pride. After the flood, the Lord commanded Noah and his sons, much in the same way as he had Adam, to “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth.” But Noah’s descendants did not obey, preferring instead to stay in one place and to erect a monument to their own pride. As Genesis 11 recounts, the Lord responded and put an end to their enterprise. He confused their language and “scattered them [the people] over the face of all the earth.”

In his address on Mars Hill, the Apostle Paul sheds further light on God’s reason for doing what he did to Babel. According to Paul, confusing their language and scattering them across the face of the earth appears to have been an act of God’s mercy. Paul explains, “And He has made form one blood every nation of men to dwell on all the face of the earth, and has determined their preappointed times and the boundaries of their dwellings, so that they should seek the Lord, in the hope that they might grope for Him and find Him” (Acts 17:26-27).

Now “nations” (Greek ethnos) here has a different, though related, meaning to the modern term “nation state.” Nations, in Paul’s usage, were what we today would call “people groups.” That is, a nation was a collection of individuals sharing a common ancestry, language and culture. A nation state, as we use that term today, although not identical to the what Paul meant by “nations”, is a closely related idea. A nation state, as it’s come to be understood, is the political expression of a particular people group.

To prove this, simply think about the nation states of the modern world. They have, historically, represented people with a common ancestry, language and culture. This is not to says that there can be no distinctions among people within a nation state. But, practically speaking, it appears that there are limits to how much diversity can exist within a nation state before that nation state itself ceases to exist.

If it’s true that God approves of nations in the people groups sense of the term, and it is, it also appears that he likewise approves of the political expression of people groups, what we have come to call the nation state. This can be seen in the radical reorganization of international relations that occurred in the century following the Protestant Reformation.

The Westphalian World Order

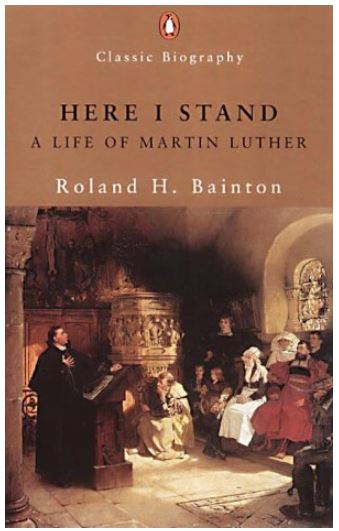

The Thirty Years’ War and the Treaty of Westphalia that settled it, are among the most important, most positive, and yet among the most forgotten by-products of the Reformation.

So forgotten are the Thirty Year’s War and the Treaty of Westphalia, that probably a large percentage of the American people has never even heard of them, let alone could tell you anything about them. But if you explain the ideas of the Treaty of Westphalia to them, not only will people generally agree with them, but they likely will say that it’s just common sense.

The Thirty Year’s War took place from 1618-1648 and was a battle between the Catholic and Protestant states of the Holy Roman Empire. Despite the guarantee of religious freedom within the Holy Roman Empire as a result of the Peace of Augsburg, Emperor Ferdinand II attempted to force citizens of the empire to follow Roman Catholic teaching. The Protestants refused to go along, and the long war, the first pan-European war, one that resulted in more than 8 million casualties, followed. In short, the good guys won, the papal forces were defeated, and the world has never been the same since.

In a nutshell, the Westphalian World Order is the principle of Mind Your Own Business (MYOB) applied to individual countries. It may surprise many people, but MYOB is a Christian principle. For example, in 2 Thessalonians, Paul writes, “For we hear that there are some who walk among you in a disorderly manner, not working at all, but are busybodies. Now those who are such we command and exhort through our Lord Jesus Christ that they work in quietness and eat their own bread” (2 Thes. 11-12).

Just as there are people who sinfully want to mind everyone else’s business, so too are there national leaders that sinfully want to mind everyone else’s business. Such was the case of Rome in the pre-Reformation period. During the Thirty Years’ War, Rome and her proxies were fighting to continue their long-held traditions of murder, theft and extortion, but received, as it were, a mortal wound from the Protestants.

But Rome, though substantially weakened, never gave up her globalist ambitions. Today, Rome is an institution recovering from that mortal wound.

The European Union as the Fourth Reich

Students of the Second World War are doubtless familiar with the term The Third Reich (German, Die Dritte Reich), which is what the Nazis called Germany under Hitler’s regime. The German word “Reich” can be translated as “empire, kingdom, or realm.”

Now calling Nazi Germany the Third Reich implies that there was a First and Second Reich. So what were these? In his book Mystery, Babylon The Great I.A.

Sadler identified the Holy Roman Empire as the First Reich (111) and the unified Germany from 1870 – 1918 as the Second Reich (214-216). The Third Reich was, of course, Nazi Germany which lasted from 1933-1945.

Sadler draws a number of parallels between the Hitler’s Third Reich and the EU, which he calls the Fourth Reich. To wit,

The EU’s attempt to create “a collectivist European State, with a single economy and currency are remarkably similar to the Nazi plan in 1942 of a united Europe under the control of Germany,

The fall of communism in eastern Europe brought about a unified Germany and the eastward expansion of the EU and NATO. A unified Germany has become the dominant force in central Europe, “revealing a disturbing parallel with the growth of the Third Reich” (264).

Czechoslovakia was split in two with the Czech Republic becoming aligned closely with Germany, mirroring Germany’s occupation of the Sudetenland in 1938,

“Austria then joined the European Union mirroring the Anschluss with Germany in 1938” (264).

Sadler concludes, “Today, through the Maastricht Treaty, national independence has been virtually abolished in favour of a European superstate, bearing an uncanny resemblance to Hitler’s Third Reich.”-

Reichs Under the Control of Rome

Though separated by time – the Holy Roman Empire got its start in the 9th century under Charlemagne – the four Reichs have this in common, they were/are all collectivist empires heavily influenced, indeed one could argue, under the control of, the Roman Catholic Church-State.

The Holy Roman Emperor was crowned by the pope.

Sadler notes that during the years of the Second Reich, “the Vatican progressively aligned itself with Germany, ensuring the balance of policies shifted away from those of Protestant Prussia towards that of a pro-Romanist German Empire, which forged an alliance with the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Austria-Hungary had long been a bastion of the Jesuits and the Church of Rome in Central and Eastern Europe” (214).

The Third Reich famously signed a concordat with Rome. For details, see Hitler’s Pope, The Secret History of Pius XII by Robert Cornwell.

The Fourth Reich, the EU, has been widely supported by the Roman Catholic Church-State. Indeed, the EU got its start with the Treaty of Rome in 1957, and the popes of Rome have consistently supported the EU.

Many have argued, and this author is in agreement with them, that the EU, properly understood is really the reincarnation of the Holy Roman Empire. As Sadler notes, the full name of the First Reich was “Sacrum Romanum Imperium Nationis Germanicae”, The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (111). Although there were many non-German nations that were part of the Holy Roman Empire, the core of the Empire’s economic and political power was Germany, and the Emperor was crowned by the pope.

[caption id="attachment_5345" align="alignnone" width="718"] Pope Francis and German Chancellor Angela Merkel shake hands on the occasion of their private audience, at the Vatican, Saturday, June 17, 2017. (L'Osservatore Romano/Pool Photo via AP)[/caption]

In like fashion, the core of the EU’s economic and political power is Germany, and the current Chancellor of Germany, Angela Merkel, though nominally Lutheran, is a close ally of the Holy See.

Brexit in Context, A Protestant Victory

With all this history in mind, Brexit can be seen in a new light. In the opinion of this author, one could argue that Brexit really ought to be seen as the culmination of a sort of second Thirty Years’ War. Worth noting, is that it took nearly the same amount of time for Nigel Farage and others to bring about Brexit – 27 years – as it did for the Allies to defeat the Catholic forces of the Holy Roman Empire.

In support of this, the idea that Brexit can be seen as a sort of second Thirty Years’ War, let us return to the Washington Post article referenced above. In response to the question, “Did religion play a part in the Brexit vote?” author James Guth responded,

Yes. If you look at the 2014 European Parliamentary Election Study, in the run-up to the Brexit vote, it’s clear that in the United Kingdom, Catholics were supportive of the E.U., as were minority religions — Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists — whereas Evangelical Protestants were the most critical of the E.U. And a lot of the surveys that were done just before and after the Brexit vote, even though they weren’t very good at identifying different religious groups, found pretty consistently that the more Protestant you were, the more critical you were of the E.U. That may have made the difference: If those Protestants had voted the way the average citizen of the United Kingdom had, Brexit wouldn’t have passed (emphasis added).

When asked, “Is Catholic support for the E.U. a result of explicit church guidance? Or is it simply an implicit cultural value?” James Guth had this very interesting response,

It’s both. The Catholic Church has explicitly supported European integration since World War II. Every pope since the end of World War II has been very supportive of the E.U. In 2014, Pope Francis gave a talk at the European Parliament about the need for the E.U. to rediscover its vision. Catholics are getting cues from the top, even if they’re subtle ones.

It’s the same story with Protestants. In the United Kingdom, you have Evangelical pastors who, on the Sunday before the Brexit referendum, were talking about how leaving the E.U. was the better Christian choice. I was at a conference in Oxford a couple of years ago, and on Sunday, I attended an Evangelical Anglican congregation. The greeter who met us at the door asked me what I was there for, and I explained that I was giving a paper on religion and European identity. He said, “Well, I think you’ve come to the wrong place. We don’t have any Europeans in this congregation.” People are getting cues like this all the time, from the clergy, from others in the congregation. It’s a pervasive cultural force, even if it’s becoming weaker (emphasis added).

Given the history of Roman Catholic attempts to reestablish its hegemony in Europe through support of the EU, and beyond through various globalist initiatives, the Brexiteers successful campaign to pull Britain out of the EU must be seen as a resounding win, not only for Great Britain, but also for all men everywhere who oppose tyranny and love liberty.

Closing Thoughts

“The kings of the Gentiles exercise lordship over them, and those who exercise authority over them are called ‘benefactors,’” said Jesus to his disciples, who were disputing among themselves about who was the greatest. Jesus reminded his disciples that it was the unbelieving pagan rulers who oppressed the people while seeking the praise of men. Jesus went on to tell them, “But not so among you,” and continued by teaching them the principle of servant-leadership. It is from this that we get the Christian idea of government as servant.

The application of Christ’s words to our present topic is easy to see. The secular rulers and popes of our day act with the same high-handed disregard for personal liberty as the ancient emperors and rulers Jesus used in his example. They pretend to be for the people, but their policies are actually destructive of the best interests of the very people they claim to represent. Nevertheless, they wish to be seen as benefactors and love to be lauded as such. This haughty spirit can be seen in the popes of Rome by their support for the EU and in the bureaucratic minions who carry out the EU’s marching orders.

In the opinion of this author, the original vote for Brexit in 2016, the election of Donald Trump that same year, the resounding victory of the Tories and Boris Johnson in 2019, and now the successful completion of Brexit should be seen as God’s grace to the people of Great Britain and the United States. This is not to suggest that everything about Brexit, Boris Johnson and Donald Trump is perfect and above reproach.

But warts and all, what the people of the Great Britain and the United States actually received, is so far superior compared to what they might have received, and perhaps even deserved to receive, that this author cannot help but see God’s gracious and providential hand at work.

In America, we dodged a real bullet in 2016, coming close to electing globalist Hillary Clinton. Had she become president, she and her globalist advisors would have quickly gone about the business of importing millions more welfare migrants and creating a permanent socialist, Democratic electoral majority. It would have been the end of America as we know it.

Had the Brexit vote gone the other way in 2016, had the Labour Party and Jerremy Corbyn carried the election in December 2019, Britain likewise would have been in a very different, and much worse, position.

This author tends to be rather pessimistic by nature, always waiting around for the next disaster. One could even argue that’s justified given the rapid downgrade in society so evident all around.

But all the bad news should not blind Christians to God’s grace, in their own lives and in broader society. God is still very much in charge, and always has been. There is not one thing in all of history that takes place but that he has brought it about both for his own glory and for the good of his own people, who were chosen in Christ before the foundation of the world.

The bottom line is this, Antichrist took a good beating from Brexit, and in that Christians can rejoice.

Let us take encouragement from this win, trusting in God to grant us wisdom and strength day by day.

![What Do You Think? [Pt. 1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a5bff8ed7bdcefb1f740198/1596470841163-FSOSCDLOHKRQB2DOGMOI/thinking.PNG)

![The Love of Many Will Grow Cold, but Do Not Grow Weary [An Encouragement]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a5bff8ed7bdcefb1f740198/1591262884744-W65ZTE5KXJQKBGI19ETL/sad+state+of+affairs+in+the+usa.jpg)